The genesis of What I (Don’t) Know About Autism came in 2016, along with my son’s autism diagnosis.

We left the private clinic that had diagnosed him with two things:

- What we thought was solid advice.

- A sense of relief that our child was the same child we’d had before. We just had an answer now for why certain things were a struggle.

My own autism diagnosis followed three years later, in June 2019, and in the time in between these two major life events, What I (Don’t) Know About Autism came into being.

What happened was that the solid advice we thought we’d left the clinic with turned out to be not so solid after all. At first, we followed it blindly, not knowing any better.

- “Find an ABA tutor.”

- “Start intensive early intervention as quickly as possible.”

- “Normalise your child to give him the best possible chance of success.”

We couldn’t find an ABA tutor. I did an ABA course instead. ABA stands for Applied Behavioural Analysis, and it is a system of training based on receiving a reward for exhibiting a desirable behaviour. Think Pavlov’s Dogs. For example, a child with autism makes ‘good’ eye contact, they are given a sweet. It’s problematic for many reasons, and so I had mixed feelings about what I learned.

We couldn’t gain access to early intervention. All doors were closed. The waiting list was three years, at least.

And we simply didn’t want to ‘normalise’ our child. We already loved him very much the way he was.

And so, we began to dig around online, to make connections to local support groups, to attend some courses, and lo and behold, we stumbled our way into the autism community.

With that discovery came the realisation that so much of the ‘expert’ information we had been given was the exact opposite of what autistic adults were saying would have helped them when they were children. Indeed, many autistic adults consider ABA to be, at best, ineffective. Just taking my previous example, ABA teaches a child with autism to make eye contact for a reward, not in order to communicate in a meaningful way. At worst, ABA is considered a form of abuse. Where the experts were talking of intervention and modification, autistic people pleaded for empathy and acceptance. Which sounds more humane to you?

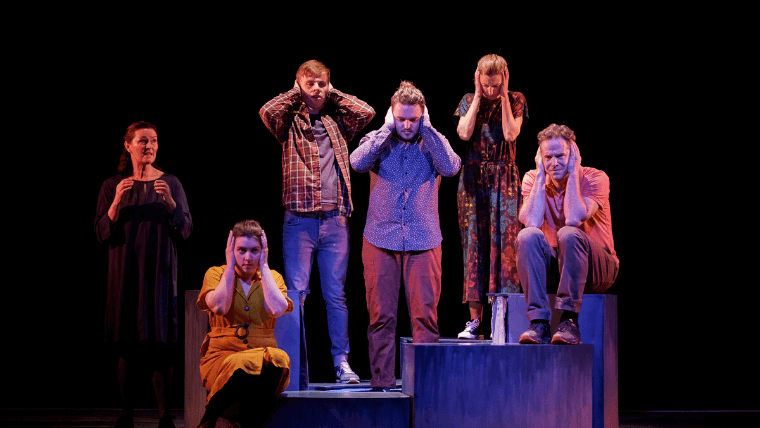

Images: Ros Kavanagh

As a parent, I wanted to learn as much as I could, as quickly as I could. I couldn’t understand why this information wasn’t getting out there. How easily we could have gone down a road that risked being so detrimental to our child.

As an artist, I wanted to find a way to get this subject matter into the public eye, because it was urgent, it was humane and it had all the ingredients for good art.

I set out to write a play with two aims: to promote autism acceptance and to celebrate autistic identity. And, at first, I had this burning idea for a play that would be set in a future world where babies are grown in labs to the genetic specifications their computer-love-matched parents have selected for them. Anomalies have been wiped out. Disorders are ancient history. But innovation is suddenly at a complete standstill. Something is missing, and that thing arrives in the form of the child of parents who decide to go about reproducing the old-fashioned way. An autistic child…

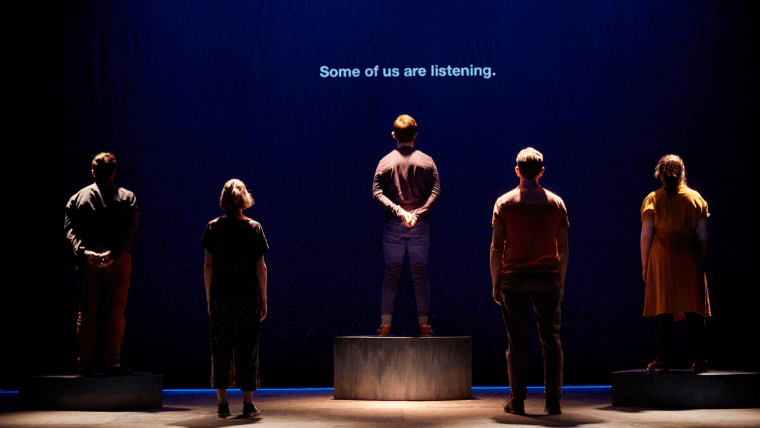

That’s what I meant to write, but something happened. I got completely sidetracked by my research, and I realised there was another play I needed to write first. A play that would act as a theatrical introduction to autism – from an autistic perspective. A play that would dispel damaging myths and reveal important truths. A play that could open up a little shaft in the mind of the viewer, through which acceptance might come pouring through.

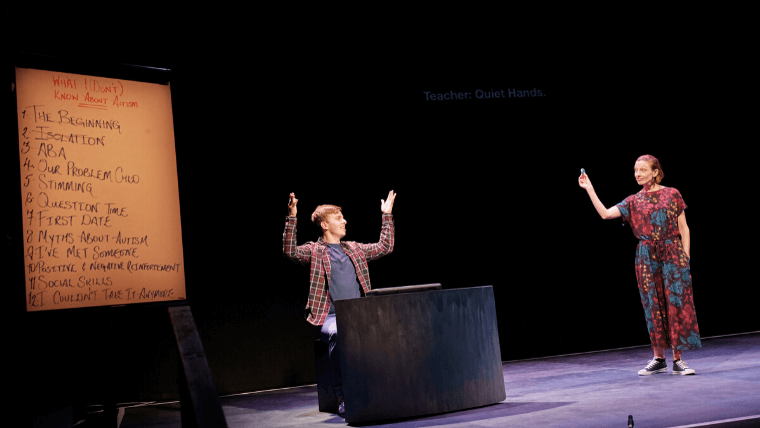

And so, I wrote the twenty-six scenes that comprise What I (Don’t) Know About Autism. Some of those scenes connect narratively to each other, some thematically, and some of them stand alone, but all of them explore different aspects of autism. The play contains over thirty characters, who can be played by just six performers (more if required). At times, the performers appear to come out of character completely to speak to each other and the audience. Indeed, there are two scenes called ‘Question Time’ that are completely improvised each night, giving the audience the opportunity to ask questions about the play. Another device that emerged during the writing process was that of the Interrupting Voice, a character who, to an extent, functions as the voice of the audience within the play, stopping the action to question, provoke or unpack what is happening onstage.

Images: Ros Kavanagh

In terms of the production, I had a few requirements from the outset…

It was crucial that at least half of the cast members would be autistic. Embracing the disability maxim ‘Nothing about us without us’, I wanted autistic voices representing autism onstage at Ireland’s national theatre. Bear in mind, I was only starting to realise at this point that I might be one of the ‘us’. But it was imperative from the outset that autistic people would be part of every aspect of the creative process.

If we were going to be celebrating autism, then I wanted autistic people to be able to come to the party. Therefore, it was going to be a relaxed performance, where traditional theatre etiquette is set aside. The house lights would remain on throughout; ear defenders would be made available to audience members; loud noises onstage would be flagged in advance; noises from the audience would be welcomed; the audience would be free to move around; and if anyone had to leave the auditorium during the performance, they would always be readmitted. They’re simple accommodations, but for some adult autistic people it meant they could come to a play for the first time ever.

Images: Ros Kavanagh

Choreography would be central to the creative process. I trained as a dancer, and so my plays tend to have a lot of movement, but the choreography had another purpose here. Stimming (or self-stimulatory behaviour) is the repetitive movements, gestures and vocal tics that autistic people commonly have. Stims might range from small things like pen-tapping or humming, to bigger things like spinning, running in specific patterns, rocking, flapping. For autistic people, stimming has important functions – self-regulating, expressing emotions, communication. Historically, stimming has been repressed by parents and teachers because it makes a child stand out as atypical. This repression had sound roots way back when standing out was enough to get you institutionalised or worse, but these days it’s more down to the fact that stimming might be distracting or embarrassing for the autistic person’s carers or guardians. But early in my writing process, I remember being at a family fun day and watching a child who was on a bouncy castle with my son. She wasn’t bouncing. Her movement was beautiful. It was rhythmic. It was stimming. It was heartfelt. It was dancing. I knew then that stimming would be an essential part of what I was writing.

Images: Ros Kavanagh

Lastly, I knew that I wanted to represent female autism, partly because I felt it was so underrepresented in the media and in the arts, and because autism in females is generally so under-diagnosed. But also, maybe because somewhere in my unconscious was the seed of an idea of where my personal journey would lead to.

What I didn’t know was how the production would be received. I thought people might be angry. I thought people might be confused. I thought maybe nobody would come.

But in fact most of the performances sold out weeks in advance. And so, I found myself on 1 February 2020, the date of our first preview at the Abbey Theatre, with an impending sense of doom – wondering what on earth I’d been thinking, wishing we could give all the tickets back, and send all copies of the book to the great big shredder in the sky.

But it was too late for that. And what followed were two extraordinary weeks, meeting autistic people, parents, teachers, health workers and just plain regular theatre goers who told us that their outlooks, their lives, the lives of their children or students, would change as a result of what they had seen. Autistic people said they felt represented onstage for the first time; parents told us they will no longer stop their children from stimming in public; teachers said they had learned more during the performance than they had at all the autism training courses they had attended; a mother realised she could finally speak to her son about his diagnosis.

Having finished the first run of the show a few weeks ago, I’m only beginning to take stock. I’m hopeful that there’s demand for the production to have another outing in Ireland and internationally, and I also hope that other companies might consider taking on the show, so that it can have as wide a reach as possible.

In terms of the text, my strong sense is that for the play to be performed, at least half the cast needs to be autistic. The script itself is a flexible blueprint. The ‘Question Time’ scenes need careful preparation and training, so that they work in performance. Apart from that, everything is up for grabs.

Images: Ros Kavanagh

This article was originally published on Nick Hern Books. The playtext of What I (Don’t) Know About Autism is out now, published in paperback and ebook formats by Nick Hern Books. To buy your copy, visit the Nick Hern Books website.